By Ani Rao MD

Among the 4,000 patients per year who receive continuous intravenous inotropic support, or inotropes for chronic heart failure (HF), two thirds receive inotropes as palliative therapy. Guidelines recommend inotropes as an option for improving symptoms, functional status, and quality of life when patients have refractory symptoms (particularly, dyspnea and fatigue) despite other palliative therapies such as diuretics, nitrates, opioids, benzodiazepines, and oxygen.

As a complex medical intervention, inotropes are not without tradeoffs. Patients require a durable central venous catheter, must carry an infusion pump 24/7, and require home health services to troubleshoot and provide support. These factors result in challenges to patients’ ability to work, travel, and participate in certain activities like swimming. Additionally, inotropes pose a barrier to hospice enrollment since many hospice agencies are not willing to continue the inotropes, forcing patients to choose between inotropes and hospice.

While inotropes have been shown to improve function and quality of life when compared to patients receiving usual HF care, they has not demonstrated a mortality benefit. Patients on inotropes as palliative therapy have an average prognosis of around 6 months, though with a large standard deviation of 6.6 months, suggesting a significant variability in treatment response. Given that most patients are prescribed inotropes as palliative therapy in the last year of life, it is important for palliative care clinicians to understand the trajectory of this therapy to inform shared decision making and promote goal concordant care.

As a palliative care clinician working at a large heart and vascular institute, I have cared for many patients on inotrope therapy. Below I depict the natural history and varying clinical scenarios of patients on inotropes to explain how the therapy influences their end-of-life HF trajectory.

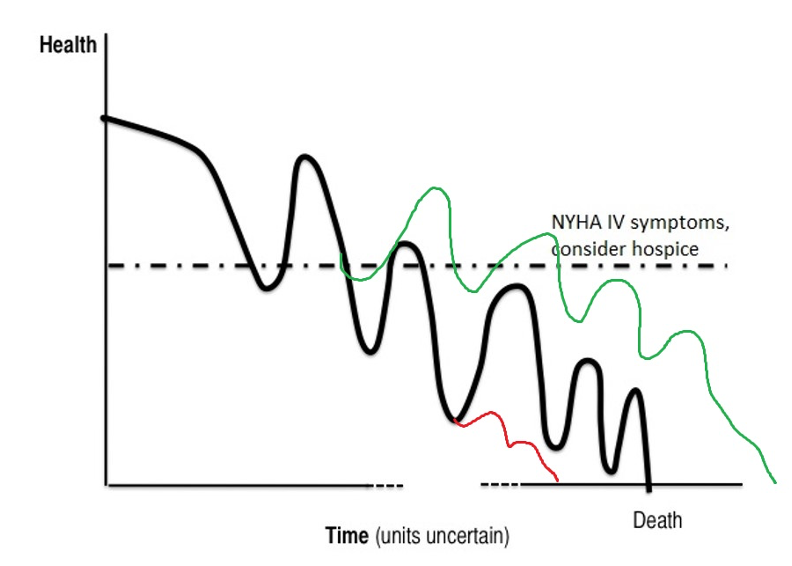

Early Initiation vs Late Initiation

Timing of inotrope initiation likely impacts the benefit of therapy. Given that HF is a disease that exists on a spectrum, presentation to a HF specialist for consideration of advanced HF therapies, including palliative inotropes, does not always occur simultaneously. Disease progression can vary depending on factors other than the patient’s HF alone, such as age, vascular disease, renal function, cognitive status, nutrition, and debility. It’s hard to know where a patient may be in the natural history of their HF. In the first figure you can see inotrope initiation at an early stage (green line) compared to initiation at a later stage (red line). Initiating inotropes at an earlier stage may offer some renal-protective factors or may improve nutritional and functional status to offer a modest improvement in quality and quantity of life compared to usual care. On the other hand, later initiation of inotropes may not confer that same benefit, owing to therapy burdens such as hypotension and arrhythmias that the patient may not tolerate (attributable to drug accumulation in the setting of worsening renal function, which are irreversible at this late stage). At this point, the patient may also not tolerate standard guideline-directed medical therapies.

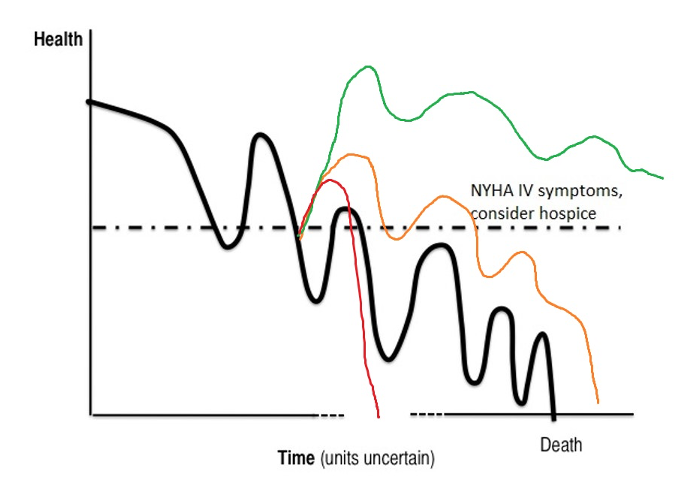

Best-case/Worst-case/Most-Likely-Case

Another way I think about timing of inotrope initiation is in the ‘best-case/worst-case/most likely-case’ model. In the second figure the most likely-case is shown here in orange (it’s the same curve as the green one above). In this situation, patients may experience an improvement in their quality of life, symptoms, a possible reduction in heart failure hospitalizations, and perhaps a slightly longer lifespan than patients on usual care (black line). On the other hand, some patients may experience a marked improvement in their exertional capacity, symptoms, and end-organ perfusion, as seen in the green line. Patients who respond robustly may actually live longer! I have known patients on palliative inotropes for over 3 years, far exceeding the average survival of all-comers with advanced heart failure. What might account for this? Perhaps these patients have better than average renal function, compared to others with advanced HF. Or perhaps they can remain tolerant of guideline directed medical therapy (GDMT) and experience the survival benefit that these medications offer. Perhaps these patients don’t have end-stage HF at all and are actually still in Stage C HF. The inotropes may be more of a bystander than an active agent. Lastly, the red line represents patients who only have a short time on inotropes, perhaps because of severe complications like bacteremia/sepsis or an arrhythmia that leads to cardiogenic shock.

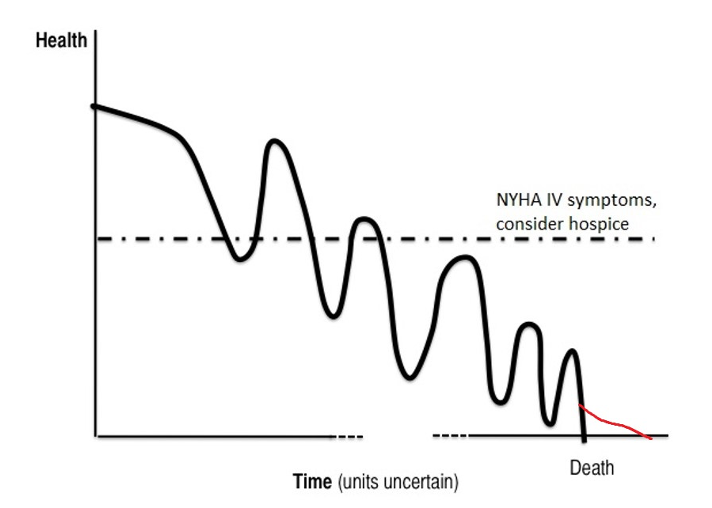

Terminal Cardiogenic Shock

Some patients present with acute coronary syndrome or cardiogenic shock and require stabilization with inotropes and possibly temporary mechanical circulatory support. These patients typically are cared for in a cardiac intensive care unit and often have multi-organ system failure. Another way to conceptualize this is that the patient has a terminal condition/prognosis and is actively dying; life sustaining medical treatments in this context can perhaps extend life by hours, days, or weeks, but is unable to reverse the underlying dying process. This is shown as the red line in the third figure. However, just as norepinephrine can improve blood pressure in a patient dying of shock, inotropes can improve hemodynamics/vital signs without reversing the underlying etiology of the shock. While the “numbers” may look better, the patient is unlikely to experience a corresponding benefit on quality of life, functional status, or symptoms. This should prompt discussions with families to center the care plan around the patient’s end-of-life. For instance, could inotropes serve as a bridge to home hospice or as a temporizing measure to allow for family to say goodbye?

Conclusions

In summary, inotropes as palliative therapy is nuanced and medically complex. It remains among the few options available for patients with end stage HF to palliate symptoms during the last phases of this illness. However, no two patients will have the same experience, and familiarization with some of the trajectories outlined above will aid clinicians in patient counseling and prognostication.

I predict that inotropes will remain a controversial treatment option among Cardiologists and Hospice and Palliative Care clinicians because of the competing risks and benefits outlined above. At present, where a clinician practices or has trained significantly affects their likelihood of recommending or withholding inotropes (clinicians in the DC metropolitan area are among the highest utilizers of inotropes!). There is renewed interest in studying novel oral inotropes, despite the concerning association with mortality found in previous trials. We could really use a prospective trial of quality of life and symptoms among patients with end-stage HF comparing intravenous inotropes with usual care to usual care alone.

Ani Rao MD is a palliative medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and Associate Professor of Medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine. His clinical and research interests focus on improving quality of life for patients with heart failure.